You Can’t Read the Other Guy’s Numbers – Covid-19 Edition

You Can’t Read the Other Guy’s Numbers

(Covid-19 Edition)

Years ago, as we studied Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A), we coined the term “You Can’t Read the Other Guy’s Numbers.” Looking at another company’s books is deceptive. In them you’ll find the familiar terms: sales, cost of goods, profit. The first time you do M&A, you think you know their meaning. But a couple of years later, in the chaos of a failed deal you learn you had no idea. The other firm’s chart of accounts and rules were perfectly correct, but different than yours. So, you were surprised, and your merger plan failed.

You can’t read the other guy’s numbers. That’s absolutely true as we try to make sense of Covid-19. We can’t understand numbers from each state or nation, and we can’t compare with other epidemics.

What we can do is think about the right questions and how uncertain we are. Sam Savage has a list of excellent questions we can’t answer. He also quotes James Hamblin in the Atlantic, “COVID-19 is, in many ways, proving to be a disease of uncertainty.”

Do we know the rate of infection? Can we compare it by different nation or state? No and no. We don’t know how many people have been asymptomatic. We don’t know the false positive rate of testing, and we don’t know how that varies by different tests. We don’t know false negative rates. In most places we don’t have random samples of the population. Distressingly, we can’t take China’s numbers at face value. A distinguished epidemiologist recently said no responsible researcher is using China’s numbers. Not all would agree with him, so that’s just one more uncertainty. You can’t read the other guy’s numbers.

Do we understand mortality? Are we counting too many Covid-19 deaths or too few? There are arguments both ways. There seem to be “excess deaths” not attributed to the virus, so perhaps those were undiagnosed Covid-19 cases. On the other hand, there may be economic incentives (like different Medicare reimbursement rates) to over count the virus as cause of death. And some doctors say the excess deaths are cause by fear of getting treatment, delay of so-called elective surgery, and delayed diagnosis. Those counting bias vary, so you can’t read the other guy’s numbers.

Do we know if lockdowns are wise? If so, do we know when it is wise? T J Rogers published a Wall Street Journal article showing there was near zero correlation between lockdown strategy and deaths per million. Does that mean lockdowns don’t work, or that strategy should vary with differences in population density, age demographics, hospital capacity… ?

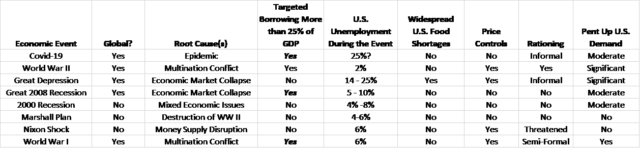

Can we predict economic impact? We can use prior econometric models, but the combination of circumstances is truly without precedent. Only twice has the U.S. borrowed at the rate we see today. In those cases, unemployment was extremely low, and we had price controls with rationing.

All this uncertainty can be very distressing. Humans aren’t wired for this, and we tend to react irrationally to it. So, what can we say with some degree of certainty?

In Texas, the weekly number of confirmed cases probably peaked about two weeks ago. Even though testing has been expanding at a 40% compounded weekly growth rate, the number of new tests per day is down. And, the ratio of negative tests has improved every week for the last month. It is now above 90%. Since we are targeting tests at vulnerable and symptomatic people, the trend is good news.

As testing expands, we should soon see more than half a million tests a week. At that point, the number of false positives may start to give us a new kind of uncertainty, but that would be welcome.

If we average death rates over a week and compare daily deaths to daily new cases two weeks ago, the death rate has fallen every week since the first deaths in March. Every death is tragic. But we can be encouraged by decreasing death rates.