Competitive Intelligence – How Good Can it Be?

Competitive Intelligence – How Good Can It Be? OR what collectible cards can teach us about intelligence in the face of uncertainty and disinformation.

Lone Star Analysis competitive intelligence professionals are a world-class cadre. They find data for our analytics and for customer use. The rest of Lone Star provides extremely specific cost-payback case studies. But not so for competitive intelligence. Customers know how good they are, but sadly this is a business where your best accomplishments can’t be told.

So, new prospects struggle to grasp what to expect. A common question is, “how good could you really be?” People under 35 often believe a web search will find nearly anything they want to know. Their elders often think if the information is not easy to find, then nefarious and illegal actions might be used. Actually, both are wrong. Lone Star is careful to avoid unethical actions, and we are not just doing web searches. We adhere to (and exceed) the SCIP code of ethics for competitive and market intelligence.

So, just how good can a private organization be without the benefit of governmental resources? The answer is Incredibly good. And the best illustration of that comes from 1929 collectible cigarette cards.

So, just how good can a private organization be without the benefit of governmental resources? The answer is Incredibly good. And the best illustration of that comes from 1929 collectible cigarette cards.

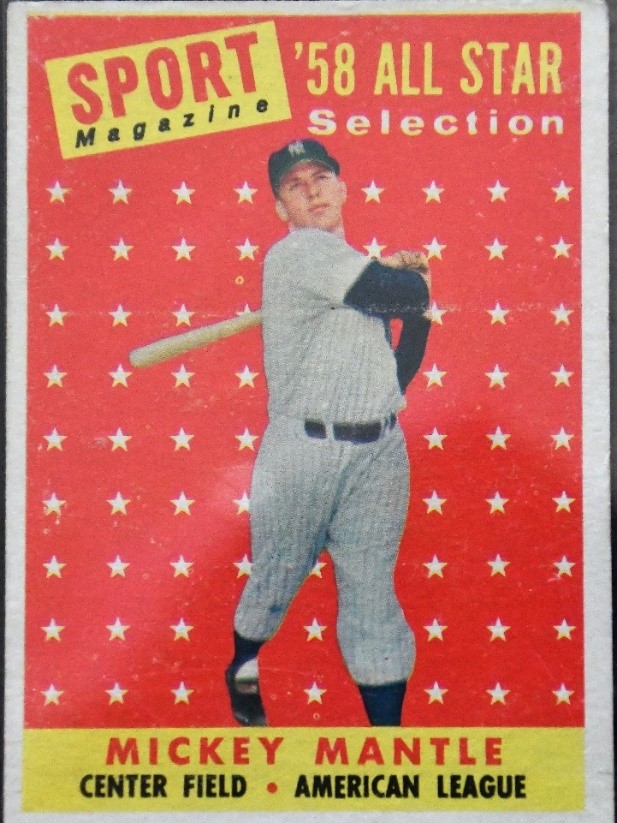

“Collectible cards” might make you think of American baseball cards. This is Mickey Mantle’s 1958 All-Star card. Baseball cards have statistics on the back. Mickey had 15 runs batted in when facing Baltimore pitches in 1957, from 20 games and 76 at-bats. He batted .365 in the ‘57 season of 144 games and 474 at-bats.

Of course, in baseball, we are confident about these numbers. They are painstakingly recorded and archived.

But most of life doesn’t have neatly compiled statistics like baseball. Generally, life is more like another kind of collectible card, less familiar to a 21st-century reader.

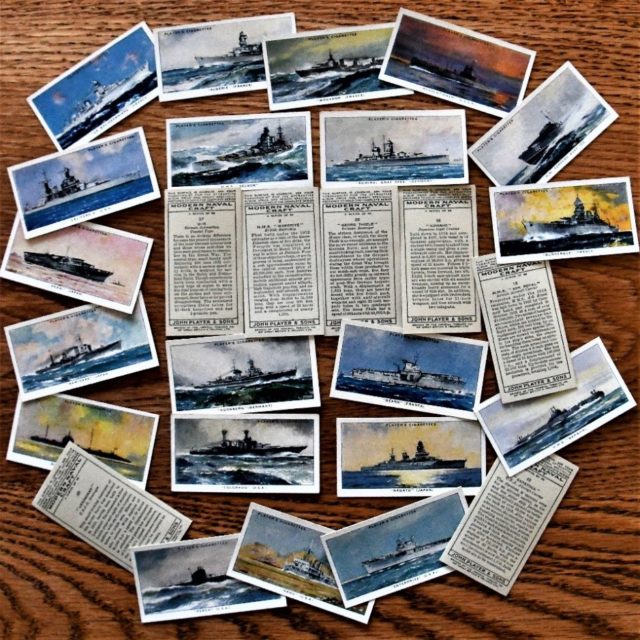

In the days before warning labels, cigarettes sometimes had trading cards in each package. These cards were incredibly diverse, not limited to sports, and their makers had to carefully research each new topic.

Take, for example, the Players Cigarette Cards from the series Modern Naval Craft 1939. This is a poignant collection, issued in March 1939, just before many of these ships would see action against each other in WW2. The Exeter (card number 6) fought the battleship Admiral Graf Spee (number 24). The Nagato (number 34) survived the war, but in 1946 she was used as a target ship during the Bikini tests, sinking very near her old foe, the Saratoga (number 48).

Ships of the British, American, Japanese, French, Italian, U.S.S.R., and German navies were included in the set, and nearly all of them were described in terms of their size or displacement.

What is interesting about Players’ displacement estimates is each card’s accuracy. This, was in spite of efforts to conceal the actual size of the ships by their respective governments. The spot-on accuracy of the cards may have been better than most naval intelligence assessments at the time.

The reason for the secrecy around ship size was in an attempt to evade the “Washington Treaty.” It bound most nations represented in the Player’s cards. The treaty’s goal was forestalling a naval arms race. It placed limitations on the number of costly battleships and aircraft carriers that could be built. For several years, it met that goal. It’s not too hard to count the number of ships built, and perhaps easier than counting what Mickey Mantle did 474 times at bat.

But it also sought to limit the size and power of ships. In that regard, it failed badly. All nations who signed the treaty cheated. All hid their cheating. Some ships, like Italy’s Trento-class cruisers, may have suffered from simple weight management problems. But most violated treaty specifications by a wide margin and by design.

So, how did the Player’s writers do better than the naval intelligence services of their day? Being in London helped. Every nation on the cards had a naval attaché staff there. A guess would be that some attachés were happy to talk about other navies. The Italian junior attaché is grateful for the attention and being asked as an expert. He was probably happy to gossip about his opinion on French and Japanese violations. Talk to eight people. Ask about two or three of their rivals, and you get a lot of information. Knowing the treaty’s displacement limits also helped. The ships were certainly no smaller than permitted.

No one seems to know exactly how Players did it. But they showed that a small private organization with limited means can be just as effective and even more effective than a state-sponsored organization.

Of course, every engagement is different. Sometimes we hit the jackpot, nearly all the time, we do better than customers expected, and once in a while, we find less than we all hoped. Your mileage may vary, but there is a reason why our customers return again and again for CI support. So, how good can an organization like this be? Incredibly good!